As we head to Nelson Mandela Square, in Johannesburg, en route home, I thought it might be appropriate to offer some thoughts about apartheid and its end.

As we head to Nelson Mandela Square, in Johannesburg, en route home, I thought it might be appropriate to offer some thoughts about apartheid and its end.

If, in the ‘sixties, apartheid looked secure, it was on far shakier foundations than it appeared. At this time, there was opposition, though given the scale of repression much of it was abroad. A number of ANC leaders had gone into exile. Especially in Britain, the anti-apartheid movement gained traction. Gradually, sporting contacts were cut off (something very painful for sports-mad white South Africans). There were popular boycotts of South African goods (see the entry on South Africa and the West, here).

For all that, it seemed that the regime was stable enough. As is often the case with repressive, de facto one-party states, the seemingly impregnable castle turned out to be something of a house of cards in the end. Through the ‘seventies and the ‘eighties apartheid South Africa was beset by problems. The first set had their roots in long-term socio-economic and demographic change. South Africa’s white population was shrinking as a proportion of its population overall. Urban South Africa’s insatiable demand for labour, the growth of the black population and the grinding poverty of rural blacks saw blacks continuing to flood into the townships, for all the pass laws, group areas and demolitions. Those blacks, facing falling real wages in the choppy economic waters of the 1970s, began to organise. Trade Unionism first stood in for political activism, then renewed it.

Apartheid, ultimately relied on three things to survive. The first was the determined support of the overwhelming majority of white South Africa, and that meant both they Afrikaners and the English. In the ‘fifties and ‘sixties, both were happy riding the gravy train. By the ‘seventies, that gravy train was drying up, and its price was becoming clear to anyone who chose to look. The third pillar was the success of its security forces in suppressing black protest.

Repressive regimes are often like a tinderbox. In all probability it was going to go off sometime. It did in 1976. Continuing urbanisation had seen the townships that surrounded all South Africa’s major cities grow rapidly (more about them in the post on Langa, here). The largest of them was Soweto. The government were always trying to control or tame the townships. Now, it was announced that from henceforth, all township children would have to be educated in Afrikaans.

Two years ago, being taken round the township of Langa, one of our party asked the young woman who was showing us round which languages she spoke. She said several African languages and English; she then added that she could speak Afrikaans, but chose not to. For her, Afrikaans was the language of the oppressor.

The schoolchildren of Soweto certainly thought so. Mass protests ensued, which in turn became the Soweto Uprising. Even Afrikaner-speaking coloured students, like our driver Wilfred, supported the protests. The authorities reacted as authorities always do, with security measures. The difference here was that it was a white security force violently attacking black and coloured protestors, many of them children. By the following year, in Soweto and beyond, 575 were dead.

The government were never able to put the lid on the security situation again. It wasn’t for want of trying. In the ten years that followed the police and armed forces resorted to beatings, torture and murder (as in the case of Steve Biko, right). Waves of arrests ensued. Still, protest was unabated. The government blamed the protests on foreign communist agitation. It launched military operations against all of its black neighbours. By the time yet another state of emergency was declared in 1986, the complete failure of security measures to suppress the popular revolt was blindingly obvious. The explanation was simple: this was a genuine, popular protest from below. Groups like the United Democratic Front or black consciousness movements carried the political fight where the banned ANC could not. Protest became unstoppable,

The government were never able to put the lid on the security situation again. It wasn’t for want of trying. In the ten years that followed the police and armed forces resorted to beatings, torture and murder (as in the case of Steve Biko, right). Waves of arrests ensued. Still, protest was unabated. The government blamed the protests on foreign communist agitation. It launched military operations against all of its black neighbours. By the time yet another state of emergency was declared in 1986, the complete failure of security measures to suppress the popular revolt was blindingly obvious. The explanation was simple: this was a genuine, popular protest from below. Groups like the United Democratic Front or black consciousness movements carried the political fight where the banned ANC could not. Protest became unstoppable,

So was the sight of white policeman or soldiers violently attacking and killing defenceless blacks. By 1986, the world had taken notice. The story of Biko and the journalist Donald Woods became a worldwide smash hit movie, Cry Freedom. America and Australia severed direct air links. The sporting boycott bit, as the did the unofficial boycott of South African goods. South African business was suffering. The gravy train was coming off the rails.

So was the sight of white policeman or soldiers violently attacking and killing defenceless blacks. By 1986, the world had taken notice. The story of Biko and the journalist Donald Woods became a worldwide smash hit movie, Cry Freedom. America and Australia severed direct air links. The sporting boycott bit, as the did the unofficial boycott of South African goods. South African business was suffering. The gravy train was coming off the rails.

At the same time as looking to security measures, the National Party made tentative efforts to reform. PW Botha’s 1983 constitution gave coloureds and Indians the vote, though they elected their own separate chambers of parliament (which were, predictably, entirely powerless and ineffectual).

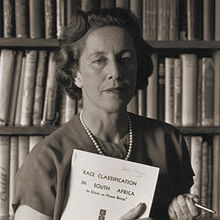

The other part of Botha’s strategy was to reinforce the unity of South Africa’s whites in support of the state. That failed. There had always been a small white opposition party, the Liberals, led by Helen Suzman, but that had been routinely crushed by the National Party juggernaut. Other white dissidents, such as the journalist Donald Woods, had fled into exile. They mattered, but not as much as what happened in the 1980s. Now, some groups that previously supported National Party rule began to have their doubts, and for some those doubts began to turn to opposition.

The other part of Botha’s strategy was to reinforce the unity of South Africa’s whites in support of the state. That failed. There had always been a small white opposition party, the Liberals, led by Helen Suzman, but that had been routinely crushed by the National Party juggernaut. Other white dissidents, such as the journalist Donald Woods, had fled into exile. They mattered, but not as much as what happened in the 1980s. Now, some groups that previously supported National Party rule began to have their doubts, and for some those doubts began to turn to opposition.

The sense that South Africa was an international pariah had become acute, and the sporting boycott genuinely hurt. Some young white men resisted the militarisation, violence and overseas aggression of the security services. The real transformation came, though, among South Africa’s business leaders, and within the National Party itself.

In 1987, a group of predominantly Afrikaner businessmen met with an ANC delegation in Senegal. Both sides called for talks. Even Botha offered to release Mandela if he renounced violence; Mandela called upon the government to do so first. By the late ‘eighties, Mandela had achieved the remarkable trick of becoming the openly acknowledged leader of South Africa’s majority population, and an international statesman, without having been seen in public for over twenty years. He had become indispensable to any solution.

In 1987, a group of predominantly Afrikaner businessmen met with an ANC delegation in Senegal. Both sides called for talks. Even Botha offered to release Mandela if he renounced violence; Mandela called upon the government to do so first. By the late ‘eighties, Mandela had achieved the remarkable trick of becoming the openly acknowledged leader of South Africa’s majority population, and an international statesman, without having been seen in public for over twenty years. He had become indispensable to any solution.

Botha had budged a tiny amount. It was far too little, far too late. An undeclared war in Angola, mounting international pressure, growing waves of popular and the fracturing of white unity meant that there was a decent chance that Apartheid’s time was up. If it was to end, and end peacefully and in a way that protected whites, suddenly the National Party needed Mandela.

And the threat of violence and chaos, and the threat to whites, seemed very real. Large scale popular protest always has the potential to turn violent, and ultimately towards brutality and even civil war (as a glimpse at the outcome of the Arab Spring has shown us). There were hard-line Afrikaner groups, such age the AWB, openly threatening violence. There were tensions between different black groups. Majority rule had come to Zimbabwe in part by war. The victorious Robert Mugabe’s strident Marxism was now giving way to violence and repression (and attacks on white farmers). Angolan independence had led to civil war. Mandela had supported violence and communism, and the communist party were part of the ANC. Now, Mandela seemed to offer the best chance of a deal that would avoid both.

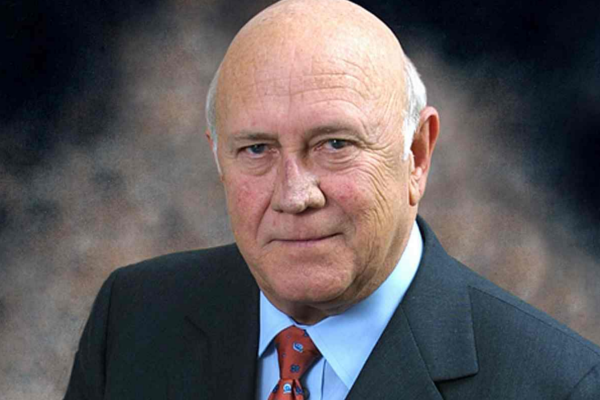

Still, Botha would not budge. Instead, he was budged. In 1988, Mandela fell ill. He was not a young man, and he had suffered years of harsh treatment at Robben Island. Were he to fall ill again, or die, any chance of a settlement might be lost. Thus, when Botha suffered a stroke in 1989, he was replaced by FW De Klerk.

De Klerk was no liberal. He was a committed National Party figure, who had supported the government throughout and remained firmly opposed to the idea of majority rule. He was also a realist. The ancien regime was finished, and South Africa’s problems were mounting. Already, Mandela had demanded talks. The new American President, George H Bush piled on the pressure: if there was no movement within six months, new sanctions would be imposed.

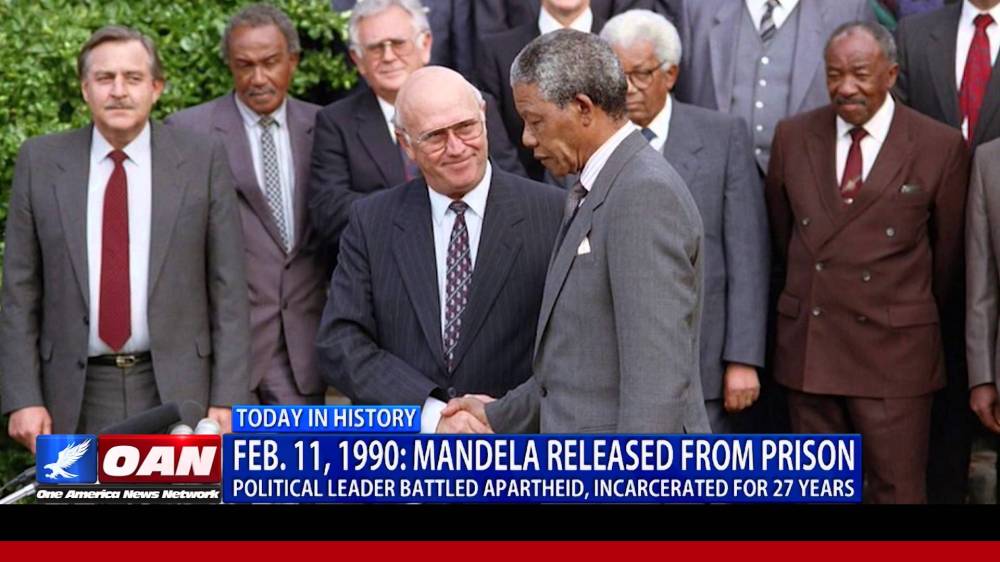

When De Klerk released Mandela in 1990, he did not envisage giving way to majority rule. That majority rule came was in large part thanks to the failure of the apartheid regime and the impact of political opposition, principally black and coloured opposition, enforcing change. What was also to the credit of the two men was that they sought a peaceful way out.

The talks could have failed. Something close to open conflict broke out between Zulus and the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal. Elements within the security services were thought to be stirring the pot. They were also encouraging right-wing Afrikaner extremism. All this reached a head when an ANC leader, Chris Hani, was assassinated. The situation was calmed by Mandela, speaking to the nation live on television.

The talks could have failed. Something close to open conflict broke out between Zulus and the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal. Elements within the security services were thought to be stirring the pot. They were also encouraging right-wing Afrikaner extremism. All this reached a head when an ANC leader, Chris Hani, was assassinated. The situation was calmed by Mandela, speaking to the nation live on television.

De Klerk might have been in office, but in many ways Mandela held the power. He pressed Home the advantage, and De Klerk agreed to majority rule: there was no peaceful alternative.

In the 1994 elections, Mandela’s ANC won a landslide. Democracy had come to South Africa.

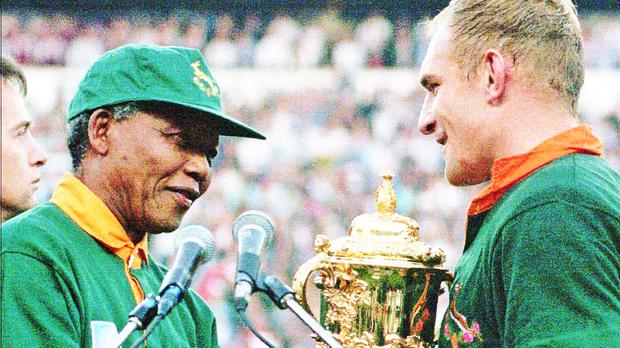

That was hardly the end of South Africa’s, or Mandela’s problems. Despite the landslide, one of the features of the 1994 election was that whites had voted overwhelmingly for the National Party, looking to it as their protector. The ANC lacked support among coloureds, and in the Cape. In particular, many Afrikaners were wholly unreconciled to the new South Africa. Famously, Mandela embraced the Rugby World Cup and The Springboks’ Afrikaner captain, François Pienaar. It was a gesture aimed at the whole of the new Rainbow nation, but above all to Afrikanerdom (see here).

Many South African whites have adjusted to the new South Africa, and have embraced the ideal of the Rainbow nation. Others have not, especially among Afrikanerdom. In both cases the failings of ANC governments have hardly helped; nor has corruption, especially in the Zuma era. Some remain unreconstructed: convinced of white superiority and the Afrikaners’ special place in history. You will see the old South African flag. Others look back to an easier world in the old days of white rule. Others fear the intentions of the ANC’s radicals, and look to the fate of Zimbabwe and especially its white farmers with horror. Many whites fear a collapse into radicalism. Some have left, some plan to; others make contingency plans, other talk about it.

Many South African whites have adjusted to the new South Africa, and have embraced the ideal of the Rainbow nation. Others have not, especially among Afrikanerdom. In both cases the failings of ANC governments have hardly helped; nor has corruption, especially in the Zuma era. Some remain unreconstructed: convinced of white superiority and the Afrikaners’ special place in history. You will see the old South African flag. Others look back to an easier world in the old days of white rule. Others fear the intentions of the ANC’s radicals, and look to the fate of Zimbabwe and especially its white farmers with horror. Many whites fear a collapse into radicalism. Some have left, some plan to; others make contingency plans, other talk about it.

We are in the 24th year of ANC rule; it is just a quarter of a century since apartheid. In historical terms, that isn’t long.

And white South Africa is still there, and shows no real sign of going away. For many Afrikaners, there is nowhere else to go. They are a part of South Africa’s turbulent history; for part of it playing an unhappy role, but also making South Africa what it is. Meeting them, most we have experienced a hospitality, friendliness, openness and courtesy that will never be bettered: they were welcoming you into their home, after all. I hope we are all grateful.

And there is hope. We have been on a hockey and Rugby tour. Earlier this year, Siya Kolosi was made Springbok captain.

Kolosi was born and raised in a township in Port Elizabeth. His mother was 16 when he was born, and he became an orphan. He was then raised by his grandmother, and was no stranger to a hungry belly.

This summer he led South Africa to a series win over England. A South African side that showed all the power and aggression we are so familiar with, but some vey impressive attacking and creative Rugby too. Kolosi is the first South African captain not to have Afrikaans or English as their first language. A few years ago the Springboks were bitterly divided along racial lines, a divide that culminated in the Afrikaner 2nd row, Geo Cronje, being kicked out for refusing to share a bedroom, shower or toilet with a coloured teammate Quentin Davids.

That has changed, and is changing. Like or not, Colossi’s selection is powerfully symbolic (he even wears the number six shirt that Mandela words on that day in 1995). We have played Afrikaners (most commonly), English, coloured and blacks on our tour. We had moments where whites (well, Afrikaans) have said things that make us uncomfortable (and should). But we have seen another side.

Let’s hope this image is emblem for the future of the Rainbow Nation.